Medieval scratch dials were cut into the stones of churches from Saxon times until around 1600, by which time they had been outcompeted by clocks. In the briefest summary, these scratch (or Mass) dials were primitive ways by which a medieval community, mostly uneducated, could tell or (more accurately) keep the time. All that was needed was a hole, a stick, a nail and some sunshine.

The concept of time as we know it did not exist early medieval times. Days were measured by the passage of the sun. Each community would have had its own daily rhythms. The earliest primitive scratch dials on country churches were the first public indicators of the day’s progress, and (later) the times of Mass. Designs gradually became more ambitious and elaborate. Scientific advances produced more technical and accurate dials, for example by graduating the space between the lines (radials) to allow for the declination of the sun; or bending the gnomon to adjust for latitude. Some later dials include decorative details. There’s a great deal more to be said on the topic, and some of it can be found at a new project called GAUDIUM SUB SOLE

Dials are often eroded, damaged, or both

The central hole for the gnomon (or ‘style’) is frequently filled in

Dials, for obvious reasons, are most usually found on the south side of a church. Favoured locations are the porch, the priest’s door, and a S. or SW. facing buttress. In some cases – especially on buttresses – more than one dial was incised. St Mary Bradford Abbas has an unusual example of large, similar dials overlapping. Repairs, as here, are often unsympathetic.

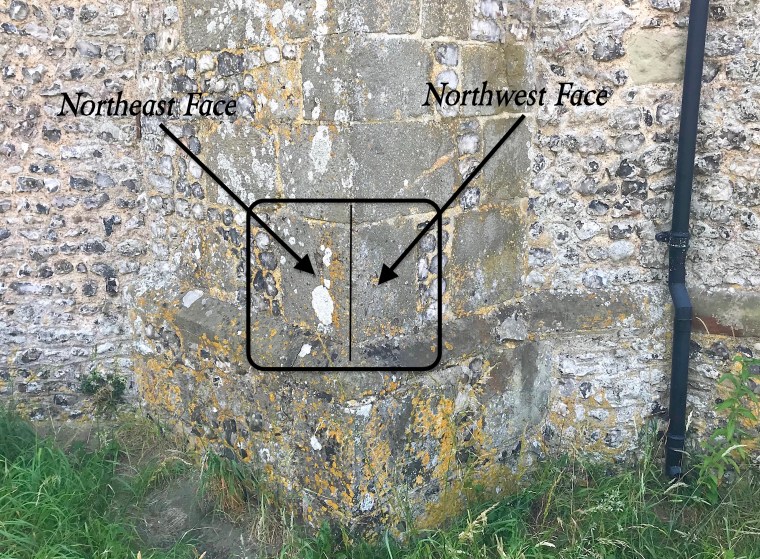

The second image shows a previously unrecorded dial, inverted, that I noticed high up on a corner tower. Stones with dials were often relocated as churches were reshaped and expanded. There’s a good example at CHARMINSTER. I’m beginning to suspect a correlation between a relocation and an inversion, almost as if to make clear the repurposing of the stone from time marker back to masonry.

A significant number of churches have multiple dials. Winterbourne Stoke (Wilts) has between 8 and 12, depending on individual interpretation. Some, including me, are keen to view any round hole as a potential style hole; and any random straight incision as a radial. Multi-dial churches are worth a close inspection. Rimpton has 4 recorded dials: I have visited twice recently and there are undoubtedly 2 more.

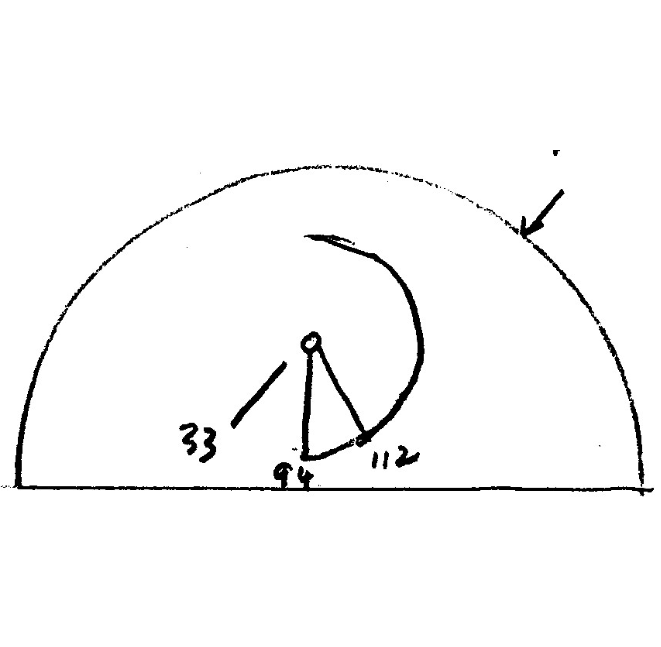

St Laurence, Holwell has 3 dials in a group on a buttress. Two are quite large and sophisticated. In the top half of the faintly encircled lower dial, there’s a small more rustic dial as shown in the diagram above (you can just see the style hole on the photo)

All six churches featured here are in the Three Valleys Benefice

Photos: Keith Salvesen sundails@gaudiumsubsole.org