Category: THEMES

BIG WIND-UP

KING DONIERT’S STONE . C9 AD

DELAYED POST

This blog was started in 2012 and was originally intended to be an omnium gatherum of specific and conceivably interesting categories. The menus below mostly had sub-menus. The blog was a spin-off from a more time-consuming effort that took priority.

I never posted very regularly, and I didn’t promote the site. Looking back at my stats, I can’t help noticing that, even by 2015, I was excusing myself for long gaps between posts. I see that 2017 was the last year that I made regular posts. In the last 5 years there have been 30 short posts – none at all for the last 2 years.

It could easily be argued (I do so with myself sometimes) that I should quietly put the blog out of its misery and delete it. However, several thousand people a year visit the site and possibly find something of interest, entertainment – or even the exact thing they are looking for.

So I have decided to leave things as they are, at least for the time being. And thanks to those who have visited, even if only once…

If you are interested in Sundials of all kinds and / or Medieval Churches, there’s a properly working blog HERE

If you have an interest in natural history elsewhere in the world – birds, reef fishes, marine mammals – try HERE

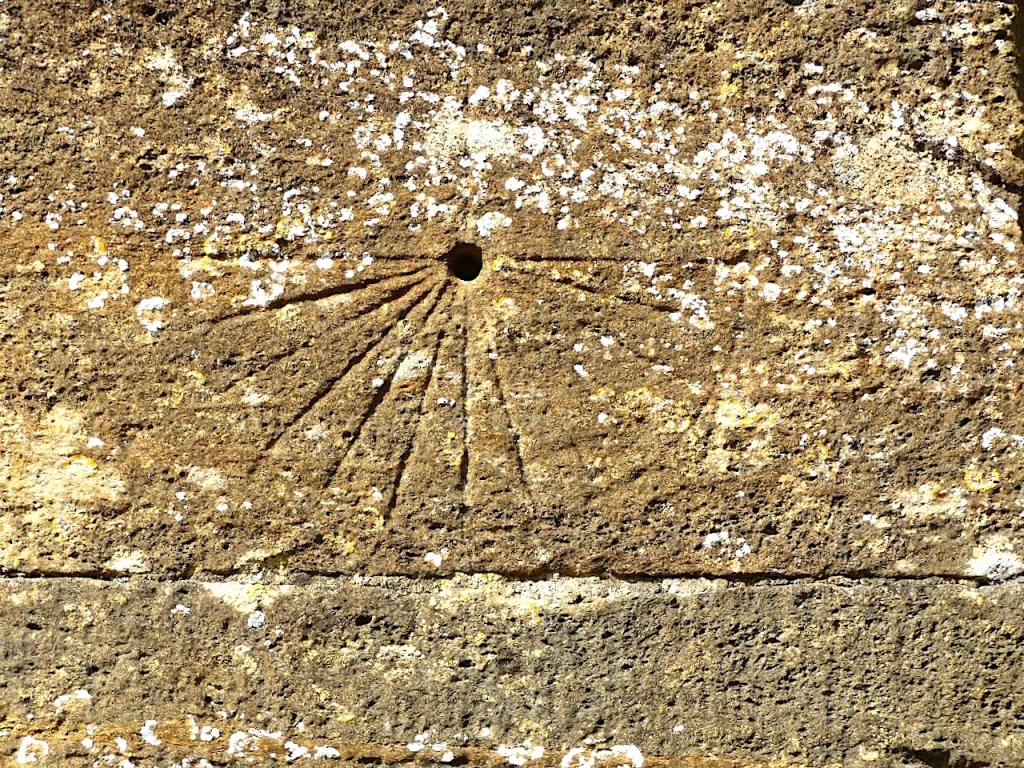

MEDIEVAL SCRATCH DIALS ON DORSET CHURCHES

Medieval scratch dials were cut into the stones of churches from Saxon times until around 1600, by which time they had been outcompeted by clocks. In the briefest summary, these scratch (or Mass) dials were primitive ways by which a medieval community, mostly uneducated, could tell or (more accurately) keep the time. All that was needed was a hole, a stick, a nail and some sunshine.

The concept of time as we know it did not exist early medieval times. Days were measured by the passage of the sun. Each community would have had its own daily rhythms. The earliest primitive scratch dials on country churches were the first public indicators of the day’s progress, and (later) the times of Mass. Designs gradually became more ambitious and elaborate. Scientific advances produced more technical and accurate dials, for example by graduating the space between the lines (radials) to allow for the declination of the sun; or bending the gnomon to adjust for latitude. Some later dials include decorative details. There’s a great deal more to be said on the topic, and some of it can be found at a new project called GAUDIUM SUB SOLE

Dials are often eroded, damaged, or both

The central hole for the gnomon (or ‘style’) is frequently filled in

Dials, for obvious reasons, are most usually found on the south side of a church. Favoured locations are the porch, the priest’s door, and a S. or SW. facing buttress. In some cases – especially on buttresses – more than one dial was incised. St Mary Bradford Abbas has an unusual example of large, similar dials overlapping. Repairs, as here, are often unsympathetic.

The second image shows a previously unrecorded dial, inverted, that I noticed high up on a corner tower. Stones with dials were often relocated as churches were reshaped and expanded. There’s a good example at CHARMINSTER. I’m beginning to suspect a correlation between a relocation and an inversion, almost as if to make clear the repurposing of the stone from time marker back to masonry.

A significant number of churches have multiple dials. Winterbourne Stoke (Wilts) has between 8 and 12, depending on individual interpretation. Some, including me, are keen to view any round hole as a potential style hole; and any random straight incision as a radial. Multi-dial churches are worth a close inspection. Rimpton has 4 recorded dials: I have visited twice recently and there are undoubtedly 2 more.

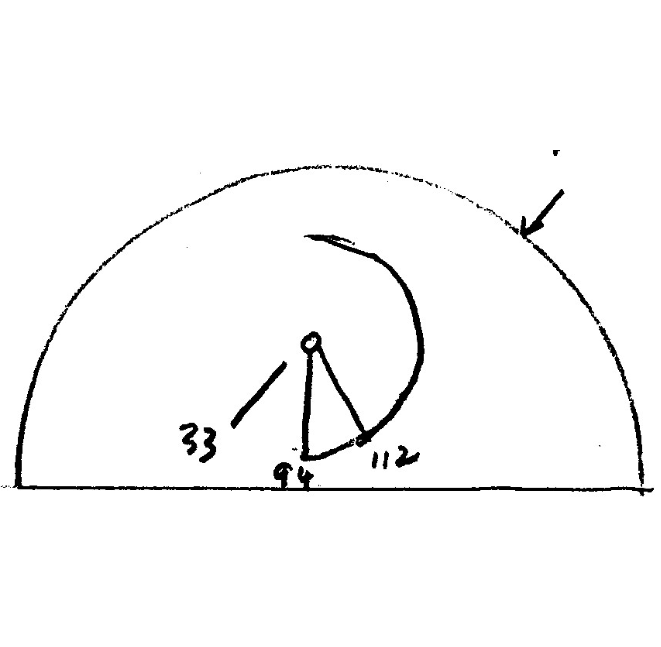

St Laurence, Holwell has 3 dials in a group on a buttress. Two are quite large and sophisticated. In the top half of the faintly encircled lower dial, there’s a small more rustic dial as shown in the diagram above (you can just see the style hole on the photo)

All six churches featured here are in the Three Valleys Benefice

Photos: Keith Salvesen sundails@gaudiumsubsole.org

GARGOYLES . ST ANDREW . YETMINSTER . DORSET

Three excellent gargoyles at the Church of St Andrew, Yetminster, where I was photographing scratch dials and medieval graffiti. There is one gargoyle at each corner of the C15 tower (the fourth was in shadow). These ‘grotesques’ were decorative in its broadest sense, and (unlike the similar hunky punks) also functional. One practical use for a gargoyle – the most usual – was as a water spout. An additional purpose was to protect the church and its precincts by repelling evil. Broadly speaking, the message they gave malevolent spirits was both ‘thou shalt not pass’ (protective) and also ‘get thee hence’ (repellent).

Most gargoyles represent creatures. Some are recognisable (usually with added malice); and others are completely monstrous. Some have both animal and human attributes. There may be disagreeable activity taking place or threatened. Good examples are the two below. In each a small human is attached to a large vicious beast, and in grave peril. In the first, a man is uncomfortably slung below the fanged beast, assessing the very long drop to the ground. In the other, the beast is equally scary and the man, semi-attached, is equally terrified. What evil spirit would take a risk with hexing this awesome (in its original meaning) church?

There’s one additional feature that I noticed only when I saw the images onscreen. In the first, the little man’s penis can be seen, and is obeying the law of gravity. The second it is not so clear-cut (as it were), but the bulge in the groin area may suggest a small and better endowed man. The display of stone genitals on medieval church carvings was yet another way in which evil could be held at bay or sent packing. The sheela-na-gig is the distaff example of the principle.

BOUNDARY STONE, LEIGH, DORSET

The village of Leigh is about 5 miles south of Sherborne. We live at the top of a steepish hill to the north. We must have been past this boundary marker on foot and by car thousands of times over the years. Yet neither of us had ever noticed it until, during a recent rainy walk, my wife pointed it out.

It’s not in itself a particularly interesting stone, but it marks a historic village boundary beside a small and sinuous stream. This is the Wriggle, later to merge with the River Yeo, join the River Parrett, and eventually debouche into the Bristol Channel.

There are no markings on the face of the stone, and I can’t trace any history of it or of similar stones locally. I haven’t found it on old OS maps. All that can be said for certain is that it considerably pre-dates its metal counterpart.

There’s no sense to be made of the cuts on the top of the stone. It’s just one of those random objects in life that one never notices until one does.

HUNKY PUNKS & GARGOYLES

HUNKY PUNKS

The image above shows a Hunky Punk. These strangely-named grotesques are found on churches in many areas of the country, especially Late Gothic ones. Usually where there is one hunky punk, there will be several (as with gargoyles). Sometimes, there may be a lone one lurking over a buttress or above a porch.

Different regions have different names for these intriguing ornaments. The name hunky punk is associated most strongly with Somerset, and more broadly with Wessex. They range from the dramatically gross to the disconcertingly lurky (see above). There’s nothing anodyne about them.

Wherever they are found, hunky punks all have a common factor: they are distinct from gargoyles. They may be very similar in design and style, but they have different functions. Gargoyles are working grotesques, usually acting as outlets for rainwater on church roofs. A length of lead pipe – or metal or (occasionally / regrettably) plastic – is the sign of a gargoyle. This usually but not invariably protrudes through the stone mouth.

A hunky punk, on the other hand, has a purely decorative function. One might dignify it with the term ‘architectural feature’. But then so is a gargoyle. Confusingly, where several grotesques are found, eg on a tower, only one or two may be functional gargoyles and the others not. Here’s an example where it is easy to tell which is which. The hunky punk appears to be praying with some distaste; the water drain (non-gargoylic) is separate.**

There are a number of theories about the purpose of hunky punks, absent a water spout function to make them useful as gargoyles. Symbols of (benign) evil to counterbalance the prevailing piety of the church precincts. Sculpture practice for trainee stonemasons. Caricatures of priests or local people; or perhaps representing Parish folklore .

My current favourite hunky punks are from St Mary’s Charminster. This church deserves a post in its own right, not least because it also has 2 medieval scratch dials (my current project), one of which was moved from the south side and replaced upside-down on the wrong face of the building.

While other more distant projects are marking time, I am currently investigating Wessex churches – strictly within prevailing Covid rules, obviously. So there’ll be more posts along these lines in due course, mostly about exterior features.

** This one may be a double bluff. It’s possible that the modern water spout to the side replaces an old pipe that emerged from the clasped hands of the priest, and channelled the rain water even as he prays. On the other hand, the aperture isn’t quite right for that. I need to check that tower again to see if any of the other 3 are water-spouting gargoyles…

Churches: Rampisham – St Michael & All Angels (1); Bradford Abbas – St Mary (2, 3); Nether Compton – St Andrew (4); Leigh – St Andrew (5); Trent – St Andrew (6); Charminster – St Mary (7, 8)

BENCHMARKS: SHERBORNE ABBEY, DORSET

Sherborne Abbey – The Abbey Church of St Mary the Virgin – is one of England’s great churches, founded in AD705. The mellow stone beauty of the exterior and the outstanding fan vaulting (let alone its other glories) secure its primacy as a place of worship, of religious and architectural study, and of inspiration for the community it serves.

It also has a clearly incised benchmark, the bathetic subject-matter of this post as foretold in the title. It’s a strangely humble feature to focus on, but the attempted revival of this blog will include such mundanities. More interesting will be the medieval scratch dials (crude early sundials carved on church walls or doorways) that I am currently working on.

All photographs © Keith Salvesen

CROSS AND HAND, BATCOMBE, DORSET

Batcombe in the heart of Dorset is a hamlet of farms, cottages, and a tiny medieval church with a fine stone screen. It is also the name of the long hill ridge that rises steeply above it. This is green and flinty Hardy country. Close to the roadside that runs along the top of the ridge is a small battered stone pillar, fairly recently awarded a small protective enclosure by Dorset Council. The spectacular 180º views from this spot on a clear day stretch to the Mendips, the Quantocks, and as far as Dunkery Beacon on Exmoor.

Batcombe in the heart of Dorset is a hamlet of farms, cottages, and a tiny medieval church with a fine stone screen. It is also the name of the long hill ridge that rises steeply above it. This is green and flinty Hardy country. Close to the roadside that runs along the top of the ridge is a small battered stone pillar, fairly recently awarded a small protective enclosure by Dorset Council. The spectacular 180º views from this spot on a clear day stretch to the Mendips, the Quantocks, and as far as Dunkery Beacon on Exmoor.

Many sources now describe this Grade II listed pillar as the Cross and Hand (the hand is now completely erased). In Hardy’s ‘Tess’ and locally, this ‘stone shaft with a rough capital, possibly pre-Conquest’ (Pevsner) is known as the Cross-in-Hand.

Many sources now describe this Grade II listed pillar as the Cross and Hand (the hand is now completely erased). In Hardy’s ‘Tess’ and locally, this ‘stone shaft with a rough capital, possibly pre-Conquest’ (Pevsner) is known as the Cross-in-Hand.

The `strange rude monolith’, as Hardy describes it, is a pivotal location in his novel. It is here that Alec d’Urberville makes Tess swear on the stone (as if had profound religious significance) never to tempt him: “put your hand upon that stone hand, and swear that you will never tempt me by your charms or ways.” Later she asks a local shepherd “What is the meaning of that old stone I have passed? Was it ever a Holy Cross?” To which the devastating answer is: “Cross—no; ‘twer not a cross! ‘Tis a thing of ill-omen, Miss. It was put up in wuld times by the relations of a malefactor who was tortured there by nailing his hand to a post and afterwards hung. The bones lie underneath. They say he sold his soul to the devil, and that he walks at times.” Tess was, in the current meaning of an older phrase, ‘gaslighted’ (or maybe ‘gaslit’).

EXTRACT FROM OFFICIAL RECORDS

‘Wayside monolithic shaft, with necking and capital. Medieval. Stone monolith of oval form, crudely tapering. It is possible that this shaft belongs to the group of pre-conquest shafts of which the pillar of Eliseg (c6) is the best known; if so the capital must have been cut down. The hand said to have been carved on one face is not traceable.’ (RCHM) Scheduled Ancient Monument Dorset No. 137 / BLB

Additional notes: Ordnance Survey benchmark on the south side