Category: CHURCHES & ABBEYS

FANS OF GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL

GREAT CLOCK . GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL

BIG WIND-UP

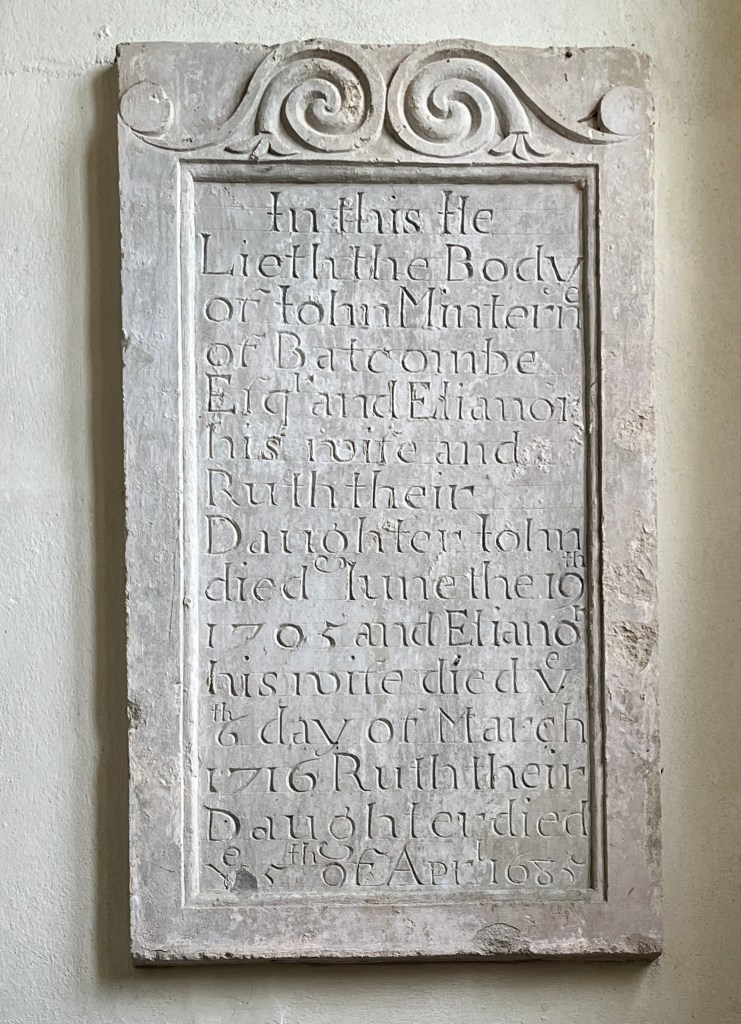

MEMORIAL TABLETS . ST MARY . BATCOMBE . DORSET

DELAYED POST

This blog was started in 2012 and was originally intended to be an omnium gatherum of specific and conceivably interesting categories. The menus below mostly had sub-menus. The blog was a spin-off from a more time-consuming effort that took priority.

I never posted very regularly, and I didn’t promote the site. Looking back at my stats, I can’t help noticing that, even by 2015, I was excusing myself for long gaps between posts. I see that 2017 was the last year that I made regular posts. In the last 5 years there have been 30 short posts – none at all for the last 2 years.

It could easily be argued (I do so with myself sometimes) that I should quietly put the blog out of its misery and delete it. However, several thousand people a year visit the site and possibly find something of interest, entertainment – or even the exact thing they are looking for.

So I have decided to leave things as they are, at least for the time being. And thanks to those who have visited, even if only once…

If you are interested in Sundials of all kinds and / or Medieval Churches, there’s a properly working blog HERE

If you have an interest in natural history elsewhere in the world – birds, reef fishes, marine mammals – try HERE

MEDIEVAL SCRATCH DIALS ON DORSET CHURCHES

Medieval scratch dials were cut into the stones of churches from Saxon times until around 1600, by which time they had been outcompeted by clocks. In the briefest summary, these scratch (or Mass) dials were primitive ways by which a medieval community, mostly uneducated, could tell or (more accurately) keep the time. All that was needed was a hole, a stick, a nail and some sunshine.

The concept of time as we know it did not exist early medieval times. Days were measured by the passage of the sun. Each community would have had its own daily rhythms. The earliest primitive scratch dials on country churches were the first public indicators of the day’s progress, and (later) the times of Mass. Designs gradually became more ambitious and elaborate. Scientific advances produced more technical and accurate dials, for example by graduating the space between the lines (radials) to allow for the declination of the sun; or bending the gnomon to adjust for latitude. Some later dials include decorative details. There’s a great deal more to be said on the topic, and some of it can be found at a new project called GAUDIUM SUB SOLE

Dials are often eroded, damaged, or both

The central hole for the gnomon (or ‘style’) is frequently filled in

Dials, for obvious reasons, are most usually found on the south side of a church. Favoured locations are the porch, the priest’s door, and a S. or SW. facing buttress. In some cases – especially on buttresses – more than one dial was incised. St Mary Bradford Abbas has an unusual example of large, similar dials overlapping. Repairs, as here, are often unsympathetic.

The second image shows a previously unrecorded dial, inverted, that I noticed high up on a corner tower. Stones with dials were often relocated as churches were reshaped and expanded. There’s a good example at CHARMINSTER. I’m beginning to suspect a correlation between a relocation and an inversion, almost as if to make clear the repurposing of the stone from time marker back to masonry.

A significant number of churches have multiple dials. Winterbourne Stoke (Wilts) has between 8 and 12, depending on individual interpretation. Some, including me, are keen to view any round hole as a potential style hole; and any random straight incision as a radial. Multi-dial churches are worth a close inspection. Rimpton has 4 recorded dials: I have visited twice recently and there are undoubtedly 2 more.

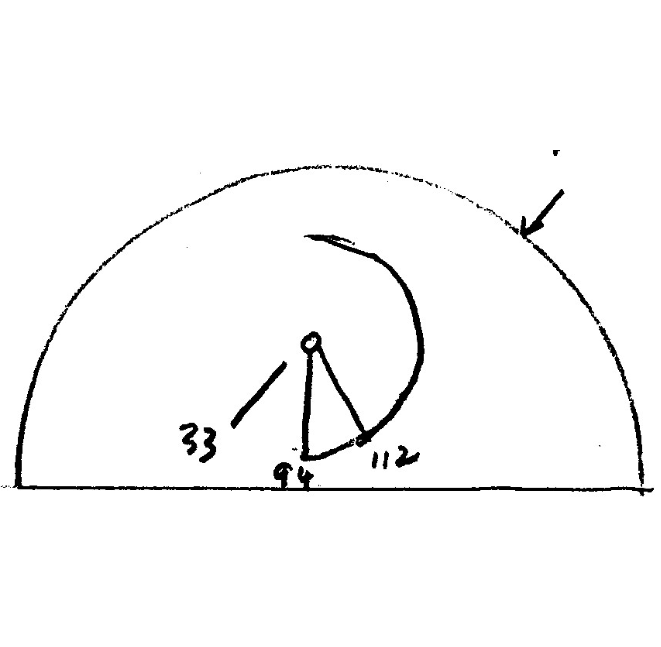

St Laurence, Holwell has 3 dials in a group on a buttress. Two are quite large and sophisticated. In the top half of the faintly encircled lower dial, there’s a small more rustic dial as shown in the diagram above (you can just see the style hole on the photo)

All six churches featured here are in the Three Valleys Benefice

Photos: Keith Salvesen sundails@gaudiumsubsole.org

GARGOYLES . ST ANDREW . YETMINSTER . DORSET

Three excellent gargoyles at the Church of St Andrew, Yetminster, where I was photographing scratch dials and medieval graffiti. There is one gargoyle at each corner of the C15 tower (the fourth was in shadow). These ‘grotesques’ were decorative in its broadest sense, and (unlike the similar hunky punks) also functional. One practical use for a gargoyle – the most usual – was as a water spout. An additional purpose was to protect the church and its precincts by repelling evil. Broadly speaking, the message they gave malevolent spirits was both ‘thou shalt not pass’ (protective) and also ‘get thee hence’ (repellent).

Most gargoyles represent creatures. Some are recognisable (usually with added malice); and others are completely monstrous. Some have both animal and human attributes. There may be disagreeable activity taking place or threatened. Good examples are the two below. In each a small human is attached to a large vicious beast, and in grave peril. In the first, a man is uncomfortably slung below the fanged beast, assessing the very long drop to the ground. In the other, the beast is equally scary and the man, semi-attached, is equally terrified. What evil spirit would take a risk with hexing this awesome (in its original meaning) church?

There’s one additional feature that I noticed only when I saw the images onscreen. In the first, the little man’s penis can be seen, and is obeying the law of gravity. The second it is not so clear-cut (as it were), but the bulge in the groin area may suggest a small and better endowed man. The display of stone genitals on medieval church carvings was yet another way in which evil could be held at bay or sent packing. The sheela-na-gig is the distaff example of the principle.

EARLY DOORS: MAIDEN NEWTON – ST MARY’S CHURCH

MAIDEN NEWTON, DORSET lies in a chalk valley at the confluence of the River Frome and its tributary the Hooke. The Church of St Mary is of particular note, dating from the C12 with earlier Saxon origins. The interior was badly damaged by fire in 2011, and has been rearranged – understandably – as a largely open space, but not fully restored. Many treasures were fortunately unscathed; one in particular received special treatment from the fire crews that saved it.

Behind the new Altar is an ancient wooden door set into the narrow arched north doorway. A plaque states that this is ‘the oldest door with original hinges in the country’. One theory is that the door is pre-Conquest, later incorporated into the Norman church built sometime between in the late C11 and 1200. Owen Morshead dates it C12; Pevsner describes it a ‘a good early door‘. So it is certainly early medieval and – whether or not actually the oldest door with original hinges – it is remarkable for its battered beauty and its overall condition.

A report of the 2011 fire and its aftermath states that “four fire crews initially used an aerial platform to avoid damaging the original doors and hinges, thought to be among the oldest in England”. On any view, it is almost certainly the oldest medieval door hung on its original hinges to have survived a major fire without damage.

HUNKY PUNKS & GARGOYLES

HUNKY PUNKS

The image above shows a Hunky Punk. These strangely-named grotesques are found on churches in many areas of the country, especially Late Gothic ones. Usually where there is one hunky punk, there will be several (as with gargoyles). Sometimes, there may be a lone one lurking over a buttress or above a porch.

Different regions have different names for these intriguing ornaments. The name hunky punk is associated most strongly with Somerset, and more broadly with Wessex. They range from the dramatically gross to the disconcertingly lurky (see above). There’s nothing anodyne about them.

Wherever they are found, hunky punks all have a common factor: they are distinct from gargoyles. They may be very similar in design and style, but they have different functions. Gargoyles are working grotesques, usually acting as outlets for rainwater on church roofs. A length of lead pipe – or metal or (occasionally / regrettably) plastic – is the sign of a gargoyle. This usually but not invariably protrudes through the stone mouth.

A hunky punk, on the other hand, has a purely decorative function. One might dignify it with the term ‘architectural feature’. But then so is a gargoyle. Confusingly, where several grotesques are found, eg on a tower, only one or two may be functional gargoyles and the others not. Here’s an example where it is easy to tell which is which. The hunky punk appears to be praying with some distaste; the water drain (non-gargoylic) is separate.**

There are a number of theories about the purpose of hunky punks, absent a water spout function to make them useful as gargoyles. Symbols of (benign) evil to counterbalance the prevailing piety of the church precincts. Sculpture practice for trainee stonemasons. Caricatures of priests or local people; or perhaps representing Parish folklore .

My current favourite hunky punks are from St Mary’s Charminster. This church deserves a post in its own right, not least because it also has 2 medieval scratch dials (my current project), one of which was moved from the south side and replaced upside-down on the wrong face of the building.

While other more distant projects are marking time, I am currently investigating Wessex churches – strictly within prevailing Covid rules, obviously. So there’ll be more posts along these lines in due course, mostly about exterior features.

** This one may be a double bluff. It’s possible that the modern water spout to the side replaces an old pipe that emerged from the clasped hands of the priest, and channelled the rain water even as he prays. On the other hand, the aperture isn’t quite right for that. I need to check that tower again to see if any of the other 3 are water-spouting gargoyles…

Churches: Rampisham – St Michael & All Angels (1); Bradford Abbas – St Mary (2, 3); Nether Compton – St Andrew (4); Leigh – St Andrew (5); Trent – St Andrew (6); Charminster – St Mary (7, 8)