Category: STONE PATTERNS

GARGOYLES . ST ANDREW . YETMINSTER . DORSET

Three excellent gargoyles at the Church of St Andrew, Yetminster, where I was photographing scratch dials and medieval graffiti. There is one gargoyle at each corner of the C15 tower (the fourth was in shadow). These ‘grotesques’ were decorative in its broadest sense, and (unlike the similar hunky punks) also functional. One practical use for a gargoyle – the most usual – was as a water spout. An additional purpose was to protect the church and its precincts by repelling evil. Broadly speaking, the message they gave malevolent spirits was both ‘thou shalt not pass’ (protective) and also ‘get thee hence’ (repellent).

Most gargoyles represent creatures. Some are recognisable (usually with added malice); and others are completely monstrous. Some have both animal and human attributes. There may be disagreeable activity taking place or threatened. Good examples are the two below. In each a small human is attached to a large vicious beast, and in grave peril. In the first, a man is uncomfortably slung below the fanged beast, assessing the very long drop to the ground. In the other, the beast is equally scary and the man, semi-attached, is equally terrified. What evil spirit would take a risk with hexing this awesome (in its original meaning) church?

There’s one additional feature that I noticed only when I saw the images onscreen. In the first, the little man’s penis can be seen, and is obeying the law of gravity. The second it is not so clear-cut (as it were), but the bulge in the groin area may suggest a small and better endowed man. The display of stone genitals on medieval church carvings was yet another way in which evil could be held at bay or sent packing. The sheela-na-gig is the distaff example of the principle.

HUNKY PUNKS & GARGOYLES

HUNKY PUNKS

The image above shows a Hunky Punk. These strangely-named grotesques are found on churches in many areas of the country, especially Late Gothic ones. Usually where there is one hunky punk, there will be several (as with gargoyles). Sometimes, there may be a lone one lurking over a buttress or above a porch.

Different regions have different names for these intriguing ornaments. The name hunky punk is associated most strongly with Somerset, and more broadly with Wessex. They range from the dramatically gross to the disconcertingly lurky (see above). There’s nothing anodyne about them.

Wherever they are found, hunky punks all have a common factor: they are distinct from gargoyles. They may be very similar in design and style, but they have different functions. Gargoyles are working grotesques, usually acting as outlets for rainwater on church roofs. A length of lead pipe – or metal or (occasionally / regrettably) plastic – is the sign of a gargoyle. This usually but not invariably protrudes through the stone mouth.

A hunky punk, on the other hand, has a purely decorative function. One might dignify it with the term ‘architectural feature’. But then so is a gargoyle. Confusingly, where several grotesques are found, eg on a tower, only one or two may be functional gargoyles and the others not. Here’s an example where it is easy to tell which is which. The hunky punk appears to be praying with some distaste; the water drain (non-gargoylic) is separate.**

There are a number of theories about the purpose of hunky punks, absent a water spout function to make them useful as gargoyles. Symbols of (benign) evil to counterbalance the prevailing piety of the church precincts. Sculpture practice for trainee stonemasons. Caricatures of priests or local people; or perhaps representing Parish folklore .

My current favourite hunky punks are from St Mary’s Charminster. This church deserves a post in its own right, not least because it also has 2 medieval scratch dials (my current project), one of which was moved from the south side and replaced upside-down on the wrong face of the building.

While other more distant projects are marking time, I am currently investigating Wessex churches – strictly within prevailing Covid rules, obviously. So there’ll be more posts along these lines in due course, mostly about exterior features.

** This one may be a double bluff. It’s possible that the modern water spout to the side replaces an old pipe that emerged from the clasped hands of the priest, and channelled the rain water even as he prays. On the other hand, the aperture isn’t quite right for that. I need to check that tower again to see if any of the other 3 are water-spouting gargoyles…

Churches: Rampisham – St Michael & All Angels (1); Bradford Abbas – St Mary (2, 3); Nether Compton – St Andrew (4); Leigh – St Andrew (5); Trent – St Andrew (6); Charminster – St Mary (7, 8)

CLOSWORTH CHURCH, SOMERSET: A TOMB & A SUNDIAL

Closworth, a small village on the Somerset / Dorset border, has a fine church with c13 origins. The village itself is best known for its historical importance as a bell-foundry between the c16 and c18, originating with the Purdue family. Few traces of the foundry remain, but some notable bells survive from its earliest days, for example in Wells Cathedral.

A quick visit to the church revealed two items of interest for this blog: a fine early c17 tomb; and an agreeable but gnomon-less sundial of uncertain date.

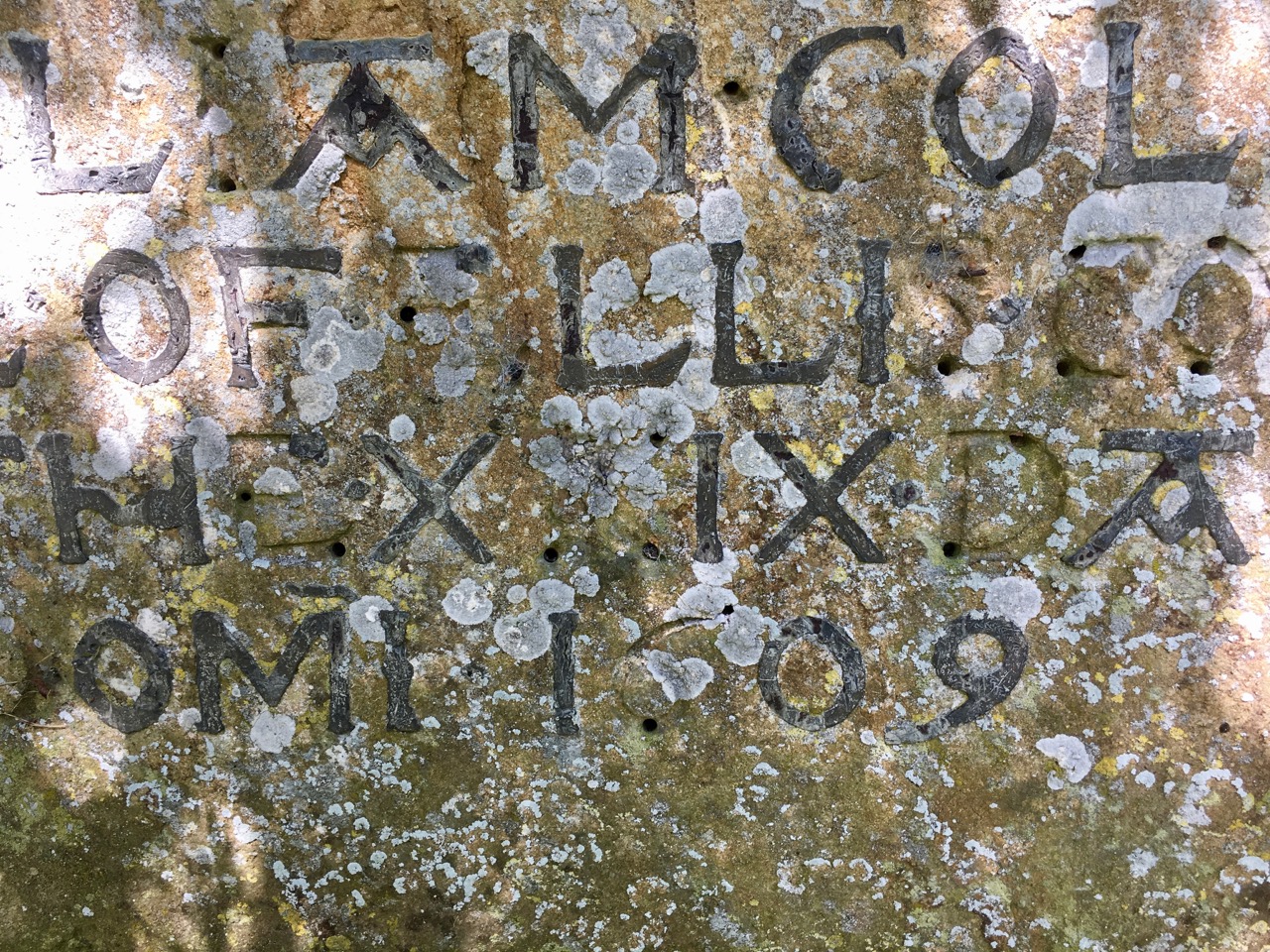

TOMB OF WILLIAM COLLINS, 1609

HERE . LYETH . THE . BODIE .

OF . WILLIAM . COLLINS . THE .

SONNE . OF . ELLIS . COLLINS . WHO

DIED . THE . XXIX . OF . IAN

ANO . DOMI . 1609

The inscription on this lichened hamstone tomb is in leaded letters set into the stone and fixed. Not all have survived the intervening centuries. I have no idea how this was achieved, but presumably the lettering was first cut into the stone; and with the stone on a horizontal surface the lead was then added to fit the incisions, and pinned in place. The result is pleasingly rustic, with some ornamentation of the As and Hs. This type of inscription-work may not be particularly unusual, but seeing this ancient tomb dappled by sunlight on a spring day made it seem special. And I always enjoy ornamental dates.

SUNDIAL: ALL SANTS CHURCH, CLOSWORTH

We didn’t notice the sundial on the way into the churchyard. Our attention had been drawn to a tall memorial to the other side of the path. On the way out, it was of course obvious – as was the lack of a gnomon. Like the tomb and the gateposts, the pillar appears to be made from the local hamstone. There isn’t much information to be gleaned from the dial itself. There’s no maker’s mark (though sometimes those are hidden on the underside of the plate). At a guess, it is c19, but any comments would be welcome.

A PUZZLING SUNDIAL IN THE PYRÉNÉES-ORIENTALES

VILLEFRANCHE-DE-CONFLENT is a small medieval walled town in Catalan country. It is watched over by Fort Liberia, one of VAUBAN‘s massive defensive constructions in this historically strategic area. The town is charming, and additionally famous for being the start of the ‘Train Jaune’, a picturesque narrow-gauge railway that climbs high into the Pyrénées. The amazing altitude rise is from 1250 ft at Villefranche to 5000 ft at the track’s summit just above the village of Mont Louis (which has its own Vauban fort)

The sundial above is high up on a house in the church square. It doesn’t exactly draw the eye, and would be very easy to miss. It’s on the house next to the Mairie (right, with the Catalan flag), below the small top windows.

TWO DIALS IN ONE

The main dial is etched and painted on cement, with roman numerals and showing hours, halves and quarters. The long gnomon is attached beneath a small sculpted head from which sun rays radiate – a simple representation of a solar deity. Above the head can be seen numbers, of which only 11 and 8 at the start, and 3 at the end can be made out with any certainty. Possibly, it is a date: the dial (which is not ancient) is otherwise undated and it is very hard to guess its age. I can find no explanation for the initials DS (top left, Gothic font) and ER (top right, normal font).

The small dial-within-a-dial shows the hours only, with arabic numerals. The gnomon points straight down. I am unsure of its purpose as a supplementary dial on the same plane, but I hope to find out.

INSCRIPTION

The words “COM MES SOL FA MES BE ESCRIC” are Catalan and mean roughly “When it is sunny, I write (show the time) well”. This rather charming inscription was apparently added around 2000 by the village pastor.

Credit: for information, Michel Lalos, who has compiled a comprehensive illustrated record of the sundials of the Pyrénées-Orientales.

ROCK FORMATIONS AT THURLESTONE, DEVON (1)

A long weekend spent at Thurlestone, Devon for a family event – a cheerful one – meant time to explore an unfamiliar area. And the rocks on the beach were quite unlike any we had seen before; certainly unlike anything on our part of the Dorset coast, 100 miles or so to the west. So I took some photos. Having no geological knowledge, I can’t say if this is part of the real – or even the flexibly tourist office-defined – “Jurassic Coast”, but I suspect not. Here are some of the strange bumpy many-hued formations.

HOOKNEY TOR & AN INFORMAL DARTMOOR LETTERBOX

Hookney Tor is a windswept rocky outcrop on Dartmoor at 414m / 1358ft ASL. It watches over the Grimspound, an intriguing bronze-age circular enclosure with the remains of 24 houses, some inhabited until medieval times. It will have a post in its own right in due course. We investigated both with our granddaughter Berry last August during a short holiday together (grandparental treat!) on Dartmoor.

After exploring the Grimspound, there is no doubt about the next achievement to tackle: a steep stony path leads invitingly from the walls to the top of the Tor. As you climb, the Grimspound quickly gets smaller below you.

Berry was not the only wild creature on the moor…

AN EXCITING DISCOVERY THAT WAS DISAPPOINTING

As we climbed, we noticed that the rocks all around were embedded with fossils. Or so we believed. We took lots of photos of these amazing calcified creatures that by some strange process were to be found at nearly 1500ft. Only later, when we did a bit of research online, did we find out the disappointing truth: not fossils, but megacrysts. The technical explanation is as follows:

The main exposure at the Tor is of megacryst granite (also known as “Giant Granite” or “Big-Feldspar Granite”). It is probably from near the roof area of the batholith. The feldpars are of perthitic orthoclase that is porphyroblastic (later replacive crystals) in origin and not phenocrysts (large crystals that have developed in the magma). In some places the southwest England granite megacrysts have been seen to develop into aplite (fine-grained quartz-feldpar veins of late origin), which is possible for porphyroblasts (developing by replacement after the veins) but not for phenocrysts (early and which should be cut through by the veins).

A DISAPPOINTING DISCOVERY THAT WAS EXCITING

Tupperware at nearly 1500ft? The plastic rubbish left behind by some idle picnicker? But no… Berry spent some time exploring the crannies of the rockiest outcrops, and in the process made her next ‘Letterbox’ discovery… [The previous year’s find is HERE]

Berry was not the first person to discover the box, which had been left by a girl from Surrey, with a message encouraging people to write in the notebook inside. This was already well-filled with the names, addresses, messages and drawings of previous explorers. There was also a strange mix of ‘souvenir’ items people had left – a car park ticket from Alton Towers, a ‘poppy day’ poppy, a couple of smoothed-out sweet wrappers, a button, and other such debris that walkers might find in their pockets… So Berry added a 1p coin, and added her contribution to the notebook. It may not have been an official Dartmoor Letterbox, but it was a lovely idea to have hidden it for others to enjoy.

Credit: photos 4, 5, first megacryst, and all agile activity by Berry

‘ALL THE VIEWS, NONE OF THE CLIMB’

In Welsh border country not far north of Hay-on-Wye are the Begwyns, modest hills in unspoilt surroundings with far views to the Black Mountains to the east and the Brecon Beacons to the south. This is National Trust land: you can see their Begwyns page HERE with a useful circular walk map. A gentle uphill stroll takes you to a feature called The Roundabout, built for the Millennium. There is a trig point nearby with magnificent views through 270º. It must be wonderful on a sunny day; ours was not, yet we could see for miles. The photos are quite poor, however…

It’s an easy ramble up from the road to The Roundabout

To the east is the northern end of the Back Mountains – Hay Bluff and Twmpa

To the south are the Brecon Beacons, with the summit of Pen-y-Fan in the clouds![]()

To the west are distant views towards Carmarthenshire

The Trig Pillar stands at 414m ASL. The first 2 views looks south to the Brecon Beacons

This view looks south east to the southern end of the Black Mountains above Crickhowell

The Trig Pillar and stone-built The Roundabout

The Trig Pillar taken from inside the Roundabout

Within The Roundabout is a stone circle with seats round it, like a medieval meeting place

Sadly there’s no view from inside The Roundabout. Here’s the inscribed Millennium Stone

PORTLAND BILL, DORSET – ROCKS & FOSSILS 1

Pulpit Rock is an artificial stack of rocks at the southern tip of Portland. It was created in the 1870s during quarrying as a relic of the industry. It is climbable and is apparently somewhere that the adventurous like to ‘Tombstone’, an activity beyond my imagining.

The flaggy flat areas near the rock are reminiscent of the ‘Flaggy Shore’ of the Burren, Co. Clare

Rock. And a pretty wheatear. There were also meadow pipits, and lots of gulls

The rock surfaces all round Pulpit Rock is known as ‘Snail Shore’, embedded with millions of snail, oyster and mollusc shells from what was once the seabed in Jurassic times. Here are a few examples, some surpassingly large.

An arty shot of Pulpit Rock to end with, taken into the sun with mixed success